Don’t you love falling into a well-crafted story, losing track of time and place, of everything but the book in your hands?

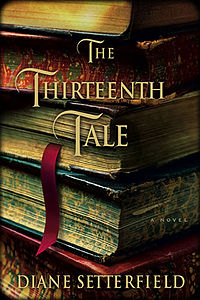

For the past couple days I’ve been deep inside the world created by Diane Setterfield in The Thirteenth Tale. It is not the type of book I typically read — it’s a gothic novel, filled with twists, violence, mystery, suspense, mental illness, ghosts, Jane Eyre references, and Angelfield, a once grand estate destroyed in a fire.

What drew me in is the golden thread running through it: a passion for books, for stories, and for the power they have to shape our lives.

Take this quote, from page 17:

“People disappear when they die. Their voice, their laughter, the warmth of their breath. Their flesh. Eventually their bones. All living memory of them ceases. This is both dreadful and natural. Yet for some there is an exception to their annihilation. For in the books they write they continue to exist. We can rediscover them. Their humor, their tone of voice, their moods. Through the written word they can anger you or make you happy. They can comfort you. They can perplex you. They can alter you. All this, even though they are dead. Like flies in amber, like corpses frozen in ice, that which according to the laws of nature should pass away is, by the miracle of ink on paper, preserved. It is a kind of magic.”

I can’t write much without spoiling some of the story, so I’ll limit myself to the novel’s basic premise. Vida Winter is England most famous and beloved living author, yet in every interview she’s given tells a different story of her past. The truth has eluded journalists for years, and she has dissuaded 22 different biographers from writing her life story. In her old age, she writes to Margaret Lea, a reclusive woman who works with her father in his antiquarian bookshop, a woman who, for fun, writes biographical essays about obscure English writers.

She has decided it is time to tell the truth, and she wants to tell it to Margaret.

Books and the lives of their authors are her world, but Margaret prefers books by writers who are long dead. She’s used to archives, not interviewing a live person.

The book is told from Margaret’s point of view, in first person, as she takes down the story of Vida Winter’s life. I found the novel haunting and in some points distressing in its darkness. That tension was relieved by characters of genuine kindness and goodness, such as Miss Winter’s housekeeper, or John the Dig.

Setterfield reserved her wit for the wily Vida Winter, who, in spite of life-threatening illness, manages quips such as, “I have written about people who don’t care for money, but I never expected to meet one. People whose lives are not balanced by a healthy love of money suffer from an appalling obsession with personal integrity.”

I do not profess to be an academic expert on gothic novels, and perhaps my senses aren’t attuned to the literary merits (or lack thereof) in the book’s convoluted and unrealistic plot. But it was gripping to the point I’ve lost track of time, the need to eat supper, and the fact that I have dishes to do. Alas, they’ll wait until morning.

This debut novel became No. 1 on The NYT Best Seller list one week after publication. It’s been made into a movie starring Vanessa Redgrave.

For more on my Friends of the Library Project (FOLP), read my post on summer resolutions and reviews for books 1, 2, 3, 4, & 5.

I will check it out! Are you going to watch the movie?

I’m afraid to watch the movie — there’s stuff that happened I really don’t want to see more clearly than I’ve already imagined!